Gestern saß ich mit einer meiner besten Freundinnen zusammen, Teresa, ihr kennt sie vielleicht von Folkdays, vor mir ein Glas Erdbeer-Secco, wie früher, weil ich noch nie Alkohol mochte, der nicht nach Limo schmeckt, unter mir meinen Periode und in mir drin: Verwirrung. Zwei Stunden und drei Buch-Tipps später wusste ich wieder, dass es gut ist, alles auszusprechen – jede noch so kleine Kleinigkeit, die irgendwo drückt. Dass es hilft, zu reden, weil Sprache nicht nur gemacht ist, um sich auszudrücken, sondern auch, um Gedanken zu sortieren. Um überhaupt verstehen zu können, was da passiert. In unseren Hirnen. In dieser Welt. Mit der Gesellschaft. Ich merkte aber auch, schon wieder: Dass Freund*innen wichtiger sind alles.

Die nachfolgenden Buch-Tipps (zumindest All About Love, Note to Self und The Man Who Sae Everything) gebe ich hiermit also ungelesen aber besten Gewissens an euch weiter. Damit wir vielleicht bald gemeinsam über das reden können, was beim Lesen hängen geblieben ist, was uns bewegt oder sogar ein wenig verstört zurück gelassen hat – vielleicht ja in einer monatlichen Buch-Club-Runde, offline statt online? Das wäre doch was. Ich denke jedenfalls mal drüber nach, wie sich so etwas tatsächlich umsetzen ließe. Bis dahin: Wer are all in this together.

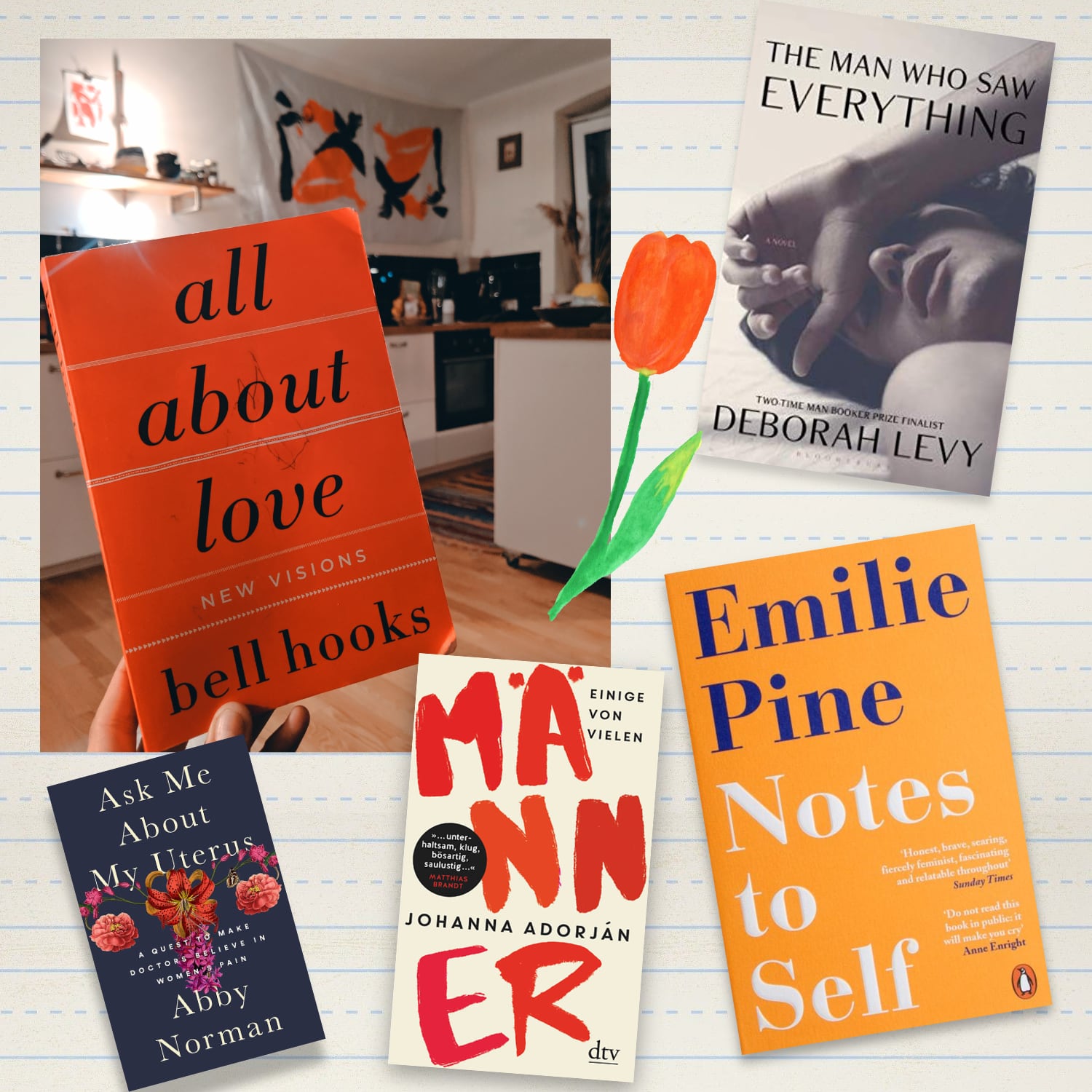

All About Love – Bell Hooks

Sieh dir diesen Beitrag auf Instagram an

„The word ‘love’ is most often defined as a noun, yet . . . we would all love better if we used it as a verb,” writes bell hooks as she comes out fighting and on fire in All About Love. Here, at her most provocative and intensely personal, bell hooks (renowned scholar, cultural critic, and feminist) skewers our view of love as romance. In its place she offers a proactive new ethic for a people and a society bereft with lovelessness.

As bell hooks uses her incisive mind and razor-sharp pen to explore the question “What is love?” her answers strike at both the mind and heart. In thirteen concise chapters, hooks examines her own search for emotional connection and society’s failure to provide a model for learning to love. Razing the cultural paradigm that the ideal love is infused with sex and desire, she provides a new path to love that is sacred, redemptive, and healing for individuals and for a nation. The Utne Reader declared bell hooks one of the “100 Visionaries Who Can Change Your Life.” All About Love is a powerful affirmation of just how profoundly she can.“

Männer – Johanna Adorján

»Ich liebe Männer. Natürlich nicht alle.« Johanna Adorján

Jochen, Oliver, Harald – fast die Hälfte der Menschheit besteht aus Männern. Immer noch machen sie viel von sich reden – warum eigentlich? Was haben sie, was andere nicht haben, und, natürlich, was haben sie nicht?

Mit dem Blick einer Frau geht Johanna Adorján durch die Welt und beschreibt, was ihr auffällt – oder vielmehr wer. Vielen dieser Männer wird man selbst schon begegnet sein, manche sind zum Glück Einzelfälle, und der eine oder andere Prominente ist auch mit dabei. Männer halt, kennt man ja.

»Dass man über etwas so Uninteressantes wie Männer so unterhaltsam und klug und mit genau der richtigen Dosis Bösartigkeit schreiben kann, das bewundere ich wirklich sehr. Und dann ist es auch noch saulustig.«

Emilie Pine – Note To Self

‚I am afraid of being the disruptive woman. And of not being disruptive enough. I am afraid. But I am doing it anyway.‘

„In this dazzling debut, Emilie Pine speaks to the business of living as a woman in the 21st century – its extraordinary pain and its extraordinary joy. Courageous, humane and uncompromising, she writes with radical honesty on birth and death, on the grief of infertility, on caring for her alcoholic father, on taboos around female bodies and female pain, on sexual violence and violence against the self. Devastatingly poignant and profoundly wise – and joyful against the odds – Notes to Self offers a portrait not just of its author but of a whole generation.“

Abby Norman – Ask Me About My Uterus

„In the fall of 2010, Abby Norman’s strong dancer’s body dropped forty pounds and gray hairs began to sprout from her temples. She was repeatedly hospitalized in excruciating pain, but the doctors insisted it was a urinary tract infection and sent her home with antibiotics. Unable to get out of bed, much less attend class, Norman dropped out of college and embarked on what would become a years-long journey to discover what was wrong with her. It wasn’t until she took matters into her own hands–securing a job in a hospital and educating herself over lunchtime reading in the medical library–that she found an accurate diagnosis of endometriosis.

In Ask Me About My Uterus, Norman describes what it was like to have her pain dismissed, to be told it was all in her head, only to be taken seriously when she was accompanied by a boyfriend who confirmed that her sexual performance was, indeed, compromised. Putting her own trials into a broader historical, sociocultural, and political context, Norman shows that women’s bodies have long been the battleground of a never-ending war for power, control, medical knowledge, and truth. It’s time to refute the belief that being a woman is a preexisting condition.“

Deborah Levy – The Man Who Saw Everything

‚An ice-cold skewering of patriarchy, humanity and the darkness of the 20th century Europe‘ – The Times

„In 1988 Saul Adler (a narcissistic, young historian) is hit by a car on the Abbey Road. He is apparently fine; he gets up and goes to see his art student girlfriend, Jennifer Moreau. They have sex then break up, but not before she has photographed Saul crossing the same Abbey Road.

Saul leaves to study in communist East Berlin, two months before the Wall comes down. There he will encounter – significantly – both his assigned translator and his translator’s sister, who swears she has seen a jaguar prowling the city. He will fall in love and brood upon his difficult, authoritarian father. And he will befriend a hippy, Rainer, who may or may not be a Stasi agent, but will certainly return to haunt him in middle age. Slipping slyly between time zones and leaving a spiralling trail, Deborah Levy’s electrifying The Man Who Saw Everything examines what we see and what we fail to see, the grave crime of carelessness, the weight of history and our ruinous attempts to shrug it off.“